The Story of Grove Hill School, updated March 2023

By Mark Smith, Omena Historical Society (for a pdf version of this essay click here)

Part One, Old Mission

The Early Days

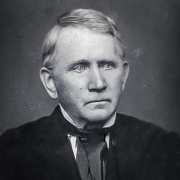

T his paper explores the history of Grove Hill School, the boarding school for local Odawa and Ojibwe people opened in Omena, or New Mission, in September 1853. (see note below text for naming conventions of indigenous peoples). Grove Hill School came into being when the first Protestant mission in the Grand Traverse area, founded by Reverend Peter Dougherty in the summer of 1838, moved their operations from Old Mission to the “New Mission” in Omena. Dougherty was originally sent to the area by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (BFM) in 1838 and eventually settled on the Old Mission Peninsula, where he would remain to preach and teach until 1852. Funding for the education of the mission Anishinaabek by the Presbyterians was provided through government monies from the 1836 treaty settlement, in which the Indians gave up vast tracts of lands in exchange for a yearly annuity payment and provisions for implements, interpreters, blacksmiths, farmers and teachers.

his paper explores the history of Grove Hill School, the boarding school for local Odawa and Ojibwe people opened in Omena, or New Mission, in September 1853. (see note below text for naming conventions of indigenous peoples). Grove Hill School came into being when the first Protestant mission in the Grand Traverse area, founded by Reverend Peter Dougherty in the summer of 1838, moved their operations from Old Mission to the “New Mission” in Omena. Dougherty was originally sent to the area by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (BFM) in 1838 and eventually settled on the Old Mission Peninsula, where he would remain to preach and teach until 1852. Funding for the education of the mission Anishinaabek by the Presbyterians was provided through government monies from the 1836 treaty settlement, in which the Indians gave up vast tracts of lands in exchange for a yearly annuity payment and provisions for implements, interpreters, blacksmiths, farmers and teachers.

It is important to note here at the outset that the Anishinabek of the Grand Traverse region were desirous to be educated, and particularly desirous to learn English, to know the law, remain in their homelands, and defend themselves in dealings with the rapacious white settlers of the area. Reverend Dougherty’s school was seen as an asset to the community, and he was welcomed especially by Chief Aghosa, his main indigenous patron. Students attended Dougherty’s school of their own free will, encouraged by their parents. Over time more Indians came to settle on “The Point”.

“The Protestant mission became an attraction of sorts to Anishinaabe communities, especially those near L’Arbre Croche, because the teacher taught in not only Anishinaabemowin, but also English. The Austrian priests near Little Traverse Bay spoke little or no English, and the Indians wanted their children to speak English.” (Fletcher, 30)

Similarly, in 1852 Chief Peshawbe and his people moved from Cross Village to the Leelanau Peninsula, precisely to take advantage of being taught by the English-speaking instructors in the schools, which they deemed to be far more useful than learning from the German speaking priests in Cross Village. Education, especially in English, was seen as a positive force for self-improvement and tribal integrity at a time when the threat of removal was still a very real threat.

Also important to note here at the outset is the fact that the Anishinaabe desired to have trusted white settlers living nearby, in order to help mediate their dealings with the larger body of settlers. During the 1836 Treaty negotiations in Washington the “chief speaker”, probably Aishquagonabe, speaking to Henry Schoolcraft, said:

“We fear that the whites who will not be our friends will come into our country and trouble us, and that we shall not be able to know where our possessions are, if we do sell our lands, it will be our wish that some of our white friends have lands among us and be associated with us. (Fletcher, 22)

Mainly these “white friends” were métis (mixed blood people), American citizens related through intermarriage who could mediate disputes with other American citizens, but benefactors like Reverend Dougherty also were seen as valued friends to be kept close at hand.

A last note pertains to agency. From the above two paragraphs it may be assumed that the Indians saw themselves as being totally dependent on the grace and favor of members of the dominant white culture, with very limited options for self-determination and very little legal recourse. However, the Odawa were anything but naïve or helpless. Their alliances with certain members of the white community were strategic ways for them to adapt, persist and prosper in their own homelands. “In 1841, Aghosa told Peter Dougherty that the Grand Traverse Anishinaabek ‘hold on to this place as a bird clings to a tree ready to fall.’” (Fletcher 38) Even though missionaries had varied luck in converting the Grand Traverse Indians to Christian farmers, the coming of the missionaries helped to make them “a group that, although still distinctly Indian, was yet able to adjust to and profit from the encroaching American economy.” (White, 10).

The historian James McClurken holds that the Anishinaabek were sophisticated in their enlistment of missionaries as allies in their attempts to avoid removal to west of the Mississippi:

“Ottawa people understood very well the process of making allies for their own benefit. As part of their campaign to remain in Michigan, they made allies of those missionaries who opposed removal and supported Ottawa efforts to purchase land. In the process, they learned that so long as they attended church services, the missionaries would help them build farms and supply them with food, clothing, and medicine. Some Ottawa adults even went to the missionary schools to learn to read and write so they could conduct their own affairs in American society.” (McClurken, 29)

According to historian Susan Gray “The Ottawa … were far less interested in becoming like white men than in learning to live as Indians in the midst of white settlement.” (Gray, 83). So, despite relying on white benefactors, the Odawa were able to maintain their own traditions and prosper within the newly emerging onrush of white settlers, at least until they were swamped by white settlers after the civil war.

After carving out some acreage for building and cultivation, Dougherty’s mission (the “Old Mission”) grew and prospered. In 1840 Reverend Dougherty ventured east to be married, returning with his new bride, Miss Maria Higgins (Sprague, and Smith). In the fall of that same year the young Andrew Blackbird was hired as apprentice blacksmith, a post he would keep for five years at a salary of $240 per year. Many years later Blackbird would write that Dougherty “was indeed a true Christian, and good to the Indians” (Blackbird 55).

In 1842, with the help of the Indians, Dougherty began to build a manse and a mission church. At the time the church was being built, Reverend Dougherty asked his congregation to make a financial contribution. Their gift to Dougherty was a large quantity of copper pennies, which Dougherty sent off to a foundry, where the pennies were used to cast a bell for the church (Craker 62). (This bell travelled with the mission to Omena, to become the bell for the new church.)

By August of 1843 Dougherty would report that his school consisted of forty Indian and eleven white children, making a total of 51 students. Basic “sounding out” and spelling were taught at first, as the building blocks of literacy. Of the 51 students, “eight read correctly in their own and our language .. The others are learning the elements [alphabet], and spelling in words of one and two syllables.” Dougherty admits to being disappointed that students did not attend more regularly but maintains that the capacity of the Indian students was “about on average” with that of the white children. In addition to the regular school, the Sabbath school regularly attracted 40 people, including Chief Aghosa, where the churchgoers were also taught to read “in their own language.. with a good degree of correctness.” Also encouraging to Dougherty was the fact that drunkenness was down and industriousness was up, thanks to the effects of the church. (Annual, 1843)

Many Roles

The work of Peter Dougherty entailed much more than preaching. Dougherty advocated for his congregation in a variety of ways, including writing letters for them, helping them apply for land patents, traveling to Mackinaw with them to receive annuity payments, tending to medical needs, carpentry, gardening, animal husbandry and generally all the labors needed to survive and prosper in a remote wilderness. From his congregation Dougherty earned the Anishinaabemowin nickname of Mic-koos, “little beaver”, reflecting his short stature and boundless energy (Craker 89).

In the early years the school averaged about 30 students, with great seasonal variations due to sickness, winter hunting, and maple syrup making. Because the school was a day school, the students were more mobile (and attended less) than if they had been attending a boarding school.

Native Language

One reason for the popularity of Reverend Dougherty’s schools is that instruction took place in English, and parents recognized the advantages of learning the language of the dominant culture. In addition to teaching in English, Dougherty also encouraged the Indians to learn to speak and write in their own language.

Sometime during his other labors he managed to make significant contributions to the study of the local Indian language. In the first years, the Upper Canadian Bible Society donated to his mission Ojibwa translations of the book of Genesis and the Gospel of John, but Dougherty soon produced books of his own. In 1844 he published A Chippewa Primer, which Schoolcraft called “of much value to the philologist, as well as being adapted to promote the advance of the pupil. (Vogel 6)

With the help of interpreters Daniel Rodd and Peter Greensky, Reverend Dougherty published other books for his Anishinaabe students, including Short Reading Lessons in the Ojibwa Language (1847), a parallel text primer, and Easy Lessons in Scripture History in the Ojibwa Language (1847).

For Dougherty the primary goal of education was the “moral” aspect; by “moral” Reverend Dougherty referred primarily to the teaching of scripture, so it is not surprising that he valued the primer he wrote for his students, Easy Lessons in Scripture History in the Ojibwa Language. Truthfully, Dougherty, like most everyone of his time, took little interest in the world views of the Odawa. He found no sense of irony in stating that “The Indian is very superstitious: he believes the Great Spirit has made him distinct from all others.” He criticized what he called the “heathen party” of unbelievers who resisted white culture:

His [the heathen Indian’s] country, his language, his customs, his religion, his medicine, his appetites and passions, are all the special bestowments of him who made him, and therefore they are best for the Indian. (Annual 1850)

Despite the somewhat condescending views in Dougherty’s assessment of indigenous culture, it is important to point out that Dougherty did not seek to actively eradicate the culture of the Anishinaabe, but he did seek to promote Christianity through bi-lingual teaching. He was certain that, when presented with alternatives to their “heathen” lifestyle, the Indians would choose Christianity. When a new translation of the Ojibwa testament came out in 1859 Dougherty requested that the BFM purchase copies because “There is quite a demand for the Ojibwa testament. It is studied more and understood better than before.” (Dougherty to Walter Lowrie, 16 Feb. 1859). Far from seeking to eradicate the native language, Dougherty understood how to use that language to promote scripture and teach “proper” behavior. Incidentally, during America’s Civil War copies of this Ojibwa bible were found among captured Anishinaabe soldiers from the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters of Company K, evidence of the importance of scripture to those soldiers and evidence of Reverend Dougherty’s influence. (Cassidy, “Both..)

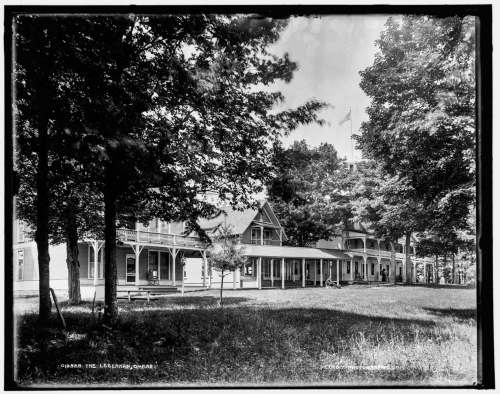

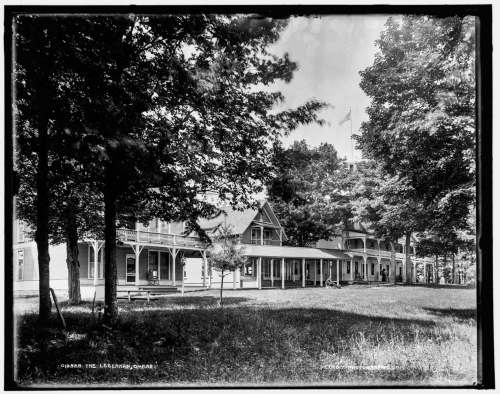

The Grove School, converted to the Hotel Leelanau

Here it is important to note an essential distinction: when the first government-run boarding schools later opened in the late 1860’s, the policy was almost always the suppression and prohibition of native languages in the schools with the goal of eradicating all ties to parents and indigenous culture. This brute force approach was seen as the best way to rapidly “civilize” the native people. Contrary to this philosophy of language suppression, Dougherty believed in the benefits of bilingualism.

In addition to their English studies, both schools [male and female] should be taught to read their own language. It is found here, as at other missions, that this does not interfere with their regular lessons in English, and it is an acquisition both pleasing and useful to their parents. (Annual 1850)

Note the inclusion of parents which continued to be a feature of the Dougherty philosophy at Grove Hill School in Omena.

Over time most of the families had taken up residence in the immediate vicinity of the old mission and worked tirelessly to produce a surplus of food. By 1847 Dougherty would write:

Six years ago the site occupied by the village was a dense thicket. The village now extends nearly a mile in length, containing some twenty log houses and some good log stables belonging to the Indians. During that period they have cleared and cultivated some two hundred acres of new gardens, besides what additions were made to the old ones. They raise for sale several hundred bushels of corn and potatoes. (Garritt 6)

Despite tremendous difficulties, and despite many setbacks and challenges, it is fair to say that Dougherty’s mission was a success. The influence of drink provided by the growing population of white settlers remained a serious issue, but all in all the mission prospered and grew. However, the land at Old Mission, having been set aside as a reservation, did not belong to the Anishinaabek of the mission. All the improvements made to the mission would be lost if the land could not be purchased and secured for those who had made the improvements. With white settlers flocking to the area to buy land, their future was uncertain.

During this time the Anishinaabek of Michigan were constantly under threat of removal to territory west of the Mississippi, a fate they desperately hoped to avoid. The goal was to find a way to stay put. The second constitution of Michigan in 1850 provided an enhanced chance for the Anishinaabek to remain. Under the provisions of the 1850 Michigan Constitution, Indians who had renounced tribal affiliations could become citizens of the state, with full voting rights (Karamanski 130). If the Indians could secure a title to some land, and if they were deemed citizens of Michigan, they would feel less threatened by removal. Unfortunately, the lands at Old Mission were not offered for immediate sale. But land on the Leelanau peninsula had recently been made available for general purchase. Gradually the Anishinaabek of Old Mission began buying up parcels and relocating to the Leelanau Peninsula, in the environs of present day Omena, where Reverend Dougherty would relocate his New Mission in 1852.

Part Two, Omena

Finding Workers

The establishment of a manual training boarding school for Anishinaabek

in Omena did not take place without extensive planning. Even before the move from a day school in Old Mission to a boarding school at the New Mission, Reverend Dougherty expressed his approval of the idea in principle but warned that in order to succeed, the mission would need to rely on “the labors of pious laymen and their wives; … suitable teachers, male and female; farmers; and families to take the charge of the boarding department” primarily because “Much precious time of the missionaries is taken up with labors that could be better performed by others” (Annual 1849). This would be a recurring theme with Dougherty over the following years as he saw his efforts increasingly devoted to working long, arduous hours of manual labor to maintain the mission, at the expense of his primary job of ministering to his flock. Dougherty rightly foresaw that running a boarding school would be a much bigger task than running a day school.

Dougherty’s warnings here can be seen as a report “from the trenches” to his superiors, who perhaps could not begin to imagine the hardships of the task. Compared to his brethren ministers out east, who were preaching on Sunday and ministering during the week, Dougherty found himself chief cook and bottle washer in a remote outpost, working long, hard hours. He described the hardships of

The separation from beloved relatives and friends, the unavoidable absence of many comforts which abound in civilized communities, the limited circle of their Christian community, the apathy, in many cases, of the benighted natives, the many, many days of teaching, and instruction, that must be endured, by our beloved brethren and sisters, in these labors of love and mercy. (Annual 1853)

However, despite Dougherty’s complaints about being constantly short staffed, he persevered.

The School Begins

Reverend Dougherty was opposed to bringing his log schoolhouse from Old Mission over to Omena (as suggested by the BFM) because he felt that the log structures did not indicate permanence to his congregation, and moreover they were not easy to heat and maintain (Dougherty, Letter to Lowrie, Sept 13th, 1851). He insisted on the construction of a new building at Grove Hill, had to advocate strongly for it, and was heavily involved in the planning and construction of it. The building at Grove Hill was meant as an assurance of commitment to permanent and long-lasting support for the whole community, children and parents.

Grove Hill School went into operation in September of 1853 with twenty boys and nine girls, and the number increased over the next year to 20 girls and 28 boys. The school was designed to accommodate 50 to 60 people, including students, workers, teachers and families. The school proved to be so popular with parents that it was soon at peak enrollment, with a waiting list for new applicants.

By 1853 Grove Hill had 20 acres under cultivation. A teacher provided agricultural training for the boys and the garden produced food to supply the mission through the winter. In order to inculcate “habits of industry” the school kept to a rigorous schedule all year round. In his first annual report from Grove Hill to Indian Agent Henry Gilbert, Dougherty described the daily regime:

The regulations of the Institution are as follows. Rise in summer at half past four and in winter at 5 o’clock am. Prayers half past five & six, breakfast at six and half past six, in summer & winter respectively. Work from breakfast to half past eight, school at nine, dinner at twelve, school at half past one, work from half past four to six, supper at six, prayers at eight pm. then the children go to bed. (Annual 1854)

Academic subjects taught at the school included reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, grammar, and philosophy. Boys also worked outdoors in the garden and girls also were instructed in “domestic labor and economy” (Annual 1854). Although by modern standards the regime of the school seems unnecessarily strict and regimented, it is important to remember that, as L. P. Hartley said “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” By modern day standards some may judge that the school was unnecessarily harsh, but in fact the strict regime was typical of other boarding schools of its time. The school was strict, but not cruel. A more salient criticism may be that of ethnocentrism, but again, it must be remembered that this was a Presbyterian school and typical of its time. We may bemoan the lack of interest in honoring native culture at the school, but we cannot expect Reverend Dougherty to behave like a man existing out of time.

Parental Inclusion

Unlike the government-run boarding schools which started up after the civil war, Dougherty’s Grove Hill School encouraged parents to visit and to be involved. The hope was that by educating the children the parents also would be lifted up. Dougherty was well aware that some Native parents were against having their children educated:

Education arms the vicious with increased power to do evil; and the minds of the Indians have often been prejudiced against the education of their children, by seeing those who had enjoyed its advantages becoming wiser only to do evil. (Annual 1850)

He rightly saw that if the Odawa were to stand a chance against the steady stream of white settlers who were rapidly flooding into the area, the native families must be helped through education:

Again: these schools are a most important and powerful agency for good, not only to the youth and children but to their parents. Instruction in these communities, to meet their wants, must be on a comprehensive scale. The white population is closing round them on every side, and everything should be done to enable them to stand side by side with their white neighbors. (Annual 1850)

Dougherty believed that the school needed to be enmeshed in the settlement because parents needed to be able to see for themselves how the school was run. Grove Hill School was open to all visitors.

To keep his flock together and protected from the sharp dealings of the white settlers, Dougherty knew it was necessary to train his students and their families in the ways of the dominant white culture. Dougherty knew that if his students were to attend a white school (where they would probably be singled out and ridiculed) they would not fare as well as if they were taught in their own setting. They lived mainly north of the school, in nearby Aghosatown. Reverend Dougherty tried to keep them close together but almost as soon as his congregation began to settle in the Omena area they started to disburse, “some choosing one place, and some another, and thus their position for the future is quite uncertain” (Annual 1851). A well-known disadvantage of the day school at Old Mission was that students were taken out whenever their parents removed to sugar camps or winter hunting grounds. The boarding school at New Mission would help address this problem, as well as the general disbursement problem of families living too far away to attend a day school. Parents were central to Dougherty’s philosophy.

Our efforts ought to regard these people as a whole and the influences which are brought to bear on them ought to reach the adults as well as the children and effect family as well as individual improvement. We are therefore very fully of the view that the mission must be in the neighborhood of the Indian Settlement.” (Dougherty, Letter to Walter Lowrie, July 30th, 1851)

The Later Years

Grove Hill School grew and prospered. For many years it was the center of learning and a place for numerous visitors and meetings, but by the time of the Civil War it was running at a loss. The gradual dispersal and scattering of Reverend Dougherty’s flock led eventually to the demise of the school. As early as 1858 Dougherty sensed that the mission would be difficult to maintain, financially, and in 1866 the BFM instructed Dougherty to sell the school, leaving only the church and associated mission. The church was kept open for another 5 years, but attendance continued to dwindle; by 1870 the writing was on the wall and in 1871 the BFM closed both the Omena and the Bear River outstation. “The organization’s precarious financial status did not allow it to continue supporting Indian missions without Indians” (Devens 107).

Dougherty’s last letters to the Corresponding Secretary of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions have an air of resignation and sadness. His friend Walter Lowrie, the previous Corresponding Secretary, died in December 1868, but Dougherty continued writing to his son, John C. Lowrie. In an undated letter from this time Reverend Dougherty looks back over 20 years and opines:

“But little change, in the aspect of things, has taken place, during the past year, except the shadows in the horizon of hope have a darker hue, and the mind as it contemplates them is less buoyant and confident, and looks to the future with a feeling of sadness.” (Dougherty 1870)

Dougherty had hoped that his mission would be a shining example of the benefits of the gospel, a civilizing influence on his flock, and a bulwark against White encroachment, but found in the end that “Intemperance is our greatest trouble and their great besetting sin” and that “As white men settle in around them the facilities and temptations to indulgence increase, and they are yielding more and more every year to these influences” (Dougherty 1870).

In 1871 Reverend Dougherty writes his last sad letter from Omena, indicating that the members of his church “feel uncomfortable about our proposed removal” and that they “offered to contribute of their means to aid in our support.” Dougherty explained that

“it was not want of support that led us to think of removing and leaving them, but the circumstances of our family growing up isolated so that they have no fair opportunity for occupation or settlement in life. They appreciate the motive. While duty to our family seems to direct us away it is painful to leave home for those for whom our lives have chiefly been spent to be scattered after we have labored so long to gather them.” (Dougherty to J. C. Lowrie, Feb. 10, 1871)

When the church in Old Mission was first built, the Indians gathered up all the pennies they had been saving and gave them to Reverend Dougherty to make a bell for their church. That bell was brought over to Omena in 1853. As Dougherty signs off for the last time, he mentions the bell in closing: “In the church is the bell and two stoves which belong to the board but I suppose they remain for the use of the Indians as long as they need them.” (Dougherty to J. C. Lowrie, Feb. 10, 1871)

After the mission was closed, the church was only sporadically opened to preaching. Occasionally Reverend George Nelson Smith from Northport would come to preach, and Alonzo Barnard also preached until 1880. By 1885 a Congregational Church was organized in Omena and the local Presbyterians joined the Congregationalists in the church (Craker). Today the church still stands proudly on the hill leading out of town. Grove Hill School was sold in 1868 and by 1885 was opened as the Hotel Leelanau, an upscale resort destination for summer residents. It was shut down in 1917 and torn down in 1929 (Holmes). Apart from a few bricks and blocks hidden in the deep weeds, nothing remains to indicate the existence of Grove Hill School.

(for a pdf version of the Power Point presentation which accompanies this essay, click here)

(Note: the term “Anishinaabek” or Anishinaabeg refers to several groups of indigenous peoples, including the Odawa and Ojibwe who feature in this paper. “Anishinaabe” is adjectival. “Anishinaabemowin” designates the language spoken. The term “Indian”, although distasteful to some, was the designation used at the time of this story and indeed the term still used by many Anishinaabek themselves. The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, for example, is still the standard nomenclature.)

Works Cited

Annual Report of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America. United States, n.p, 1929.

Blackbird, Andrew J. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan: A Grammar of Their Language, and Personal and Family History of the Author. Petoskey, Mich: Little Traverse Regional Historical Society, 1970.

Cassidy. Michelle. “The More Noise They Make: Odawa and Ojibwe Encounters with American Missionaries in Northern Michigan, 1837-1871.” Michigan Historical Review, vol. 38, no. 2, Central Michigan University, 2012, pp. 1–34.

Cassidy, Michelle K. “Both the Honor and the Profit”: Anishinaabe Warriors, Soldiers, and Veterans from Pontiac’s War through the Civil War.” https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/133496

Craker, Ruth. First Protestant Mission in the Grand Traverse Region. Rivercrest House, 1979.

Dougherty, Peter, “Dougherty Papers,” 1838-1872, Presbyterian Historical Society, online.

Devens, Carol. Countering Colonization, Native American Women and Great Lakes Missions, 1630-1900.

Fletcher, Matthew. The Eagle Returns. Michigan State University Press, 2012.

Garritt, Joshua Bolles. Historical sketch of the missions among the North American Indians : under the care of the Board of foreign missions of the Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia: Women’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church, 1881.

Gray, Susan E. “Limits and Possibilities: White-Indian Relations in Western Michigan in the Era of Removal.” Michigan Historical Review 20 (1994): 71-91.

Holmes, Amanda. Omena a Place in Time a Sesquicentennial History 1852–2002. 1st., The Omena Historical Society, 2003.

Karamanski, Theodore J. Blackbird’s Song. Michigan State University Press, 2012.

McClurken, James M. “The Ottawa.” In People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa,

Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan. Grand Rapids: Intertribal Council of

Michigan, 1986.

Singer, Eliot, “Mission Period, Grand Traverse, Epistolary,” Ethno and Superior

History, picaresquescholar.wordpress.com, accessed February 2023.

Smith Family papers (H02-1465.50), The Joint Archives of Holland, Hope College, Holland, MI.

Sprague, Elvin Lyons, and Seddie Powers Smith. Sprague’s History Of Grand Traverse And Leelanaw Counties, Michigan. B.F. Bowen, 1903.

Vogel, Virgil V. “The Missionary as Acculturation Agent.” Michigan History, vol. 51, no. 3, 1967.

White, Richard. “Ethnohistorical Report on the Grand Traverse Ottawas.” Unpublished manuscript, 1991.

Attached to Colonel DeLand’s First Michigan Sharpshooters was a company of civilized Indians who won fame at Spottsylvania. On that bloody 9th of May, 1864, the Federal line, advancing with a cheer, met the charging enemy in a dense thicket of pines, and in the hand-to-hand struggle that followed, the Union forces were slowly forced back. The First Michigan Sharpshooters was doing its best to hold the ground. Every now and then the Confederates would fight their way up to the battery and lay hold of the cannon to turn them upon the Union forces. But to touch one of those guns meant instant death at the hands of the sharpshooters. In this desperate encounter, the little band of Indians was commanded by Lieutenant Graveraet…. Under a perfect storm of lead their number seemed to melt away, but there was no sign of faltering. Sheltering behind trees, they poured volley after volley at the zealous foe, and above the din of battle their war-whoop rang out with every volley. At dusk the ammunition gave out, but with the others the Indians ran forward at the shout of “Give them steel boys!” from the twice wounded but still plucky Colonel Deland.

Attached to Colonel DeLand’s First Michigan Sharpshooters was a company of civilized Indians who won fame at Spottsylvania. On that bloody 9th of May, 1864, the Federal line, advancing with a cheer, met the charging enemy in a dense thicket of pines, and in the hand-to-hand struggle that followed, the Union forces were slowly forced back. The First Michigan Sharpshooters was doing its best to hold the ground. Every now and then the Confederates would fight their way up to the battery and lay hold of the cannon to turn them upon the Union forces. But to touch one of those guns meant instant death at the hands of the sharpshooters. In this desperate encounter, the little band of Indians was commanded by Lieutenant Graveraet…. Under a perfect storm of lead their number seemed to melt away, but there was no sign of faltering. Sheltering behind trees, they poured volley after volley at the zealous foe, and above the din of battle their war-whoop rang out with every volley. At dusk the ammunition gave out, but with the others the Indians ran forward at the shout of “Give them steel boys!” from the twice wounded but still plucky Colonel Deland.